When you live in a country but don’t fully understand the language, there are times when you can’t tell the difference between a word and a name.

Take for instance, the first time I went sailing in Mazury. In the late afternoon, the rest of the crew would discuss in which port we would spend the night: ‘We could stay in Mikołajki, or go back to Wierzba or there’s always Trzcina.’ During the trip, I was surprised that Trzcina was always an option – whether we were in the northern lakes or down in the south. ‘Wherever this port of Trzcina is,’ I thought, ‘it must be pretty central because it’s only a couple of hours sailing from anywhere in the Masurian Lakes!’

It’s no different on the road.

In the same way that I thought Trzcina (reeds) was a port, a foreigner coming to Poland for the first time might think that Wita is name of a town in Poland. I’ve seen quite a few road signs on which the word Wita is printed in a bigger, bolder font that the actual place name.

Either that or a foreigner might think that Wita is another word to define a town like Dolny or Wielki. ‘We didn’t get much of a welcome in Olsztyn Wita so why don’t we look for some accommodation in Olsztyn instead?‘

Indeed, this is part of a wider issue for a non-native learner – in the final kilometre before any Polish town there are so many billboards, welcome signs, banners and advertisements that you can be overwhelmed.

So to help, I’ve prepared this short guide to arriving or leaving a Polish town:

Arriving

- wita / witamy = either the town (wita) or its people (witamy) are welcoming you. Personally, I’ve always felt that witamy is a warmer version because it comes from the people. How exactly a town can welcome anyone I’ve never figured out.

- zaprasza / zapraszamy = in this case, either the town or its inhabitants are inviting you over, but don’t worry, you are not expected to bring a gift.

- miasto monitorowane = this literally means that the town uses surveillance equipment and often comes right after the witamy sign. Together these signs mean, ‘you’re welcome, but keep your hands where we can see them!’. Basically, the authorities don’t trust you not to break the law as you pass through.

- warto zobaczyć – this presents three things that are worth seeing in the town. Always disregard the last one, it’s just there to make up the numbers.

- witamy na ziemi…/ ziemia…wita = often a region or jurisdiction will welcome you, e.g. witamy na ziemi świętokrzyskiej. Foreigners might panic at first, thinking this is a message for aliens, welcoming them to the Planet Earth. Don’t worry, it just means ‘welcome to the land of…‘

- miasta partnerskie – these are other places with which this town is twinned. If you’ve never heard of any of the towns mentioned, don’t worry, no one has!

- EU Funds – finally, you might see something that looks more like an enlarged document than a street sign. You can ignore this, it’s just a receipt showing who paid for the pavement.

One challenge with these signs is that they tend to be covered in graffiti, so you might not know which town you’re in, but you will know which football team is trending.

Leaving

It’s the same story when you’re leaving town. Quite wisely, most towns don’t invest too much effort to say goodbye, however, there are some things it’s worth bearing in mind:

- żegna / żegnamy – to me, this is more personal than do zobaczenia, especially żegnamy. However, if the town welcomed you on the way in (wita), but the people are saying goodbye (żegnamy), then it means that they’re glad to be rid of you.

- zapraszamy ponownie – the townsfolk are inviting you back. However, if you noticed a miasta monitorowane sign on the way in and you broke a few driving laws, then I wouldn’t go back if I were you.

- termination sign – in Poland, when leaving a town, there is a sign showing the town’s name with a red line through it. This looks very official as if the town just got cancelled by some bureaucracy. Don’t worry, the town will continue to exist, just not for you. We don’t have such signs in the UK. You just drive out of town without any fanfare. In Polish, there’s an idiom wyjść po angielsku (to leave in an English way) which means to ‘leave without saying goodbye to anyone‘. The same applies to towns and villages in the UK – they don’t say goodbye either.

Billboards & Banners

Finally, a word about billboards and banners. Polish towns extend a warm welcome, but their businesses welcome you and your wallet even more warmly. I must admit that there are so many billboards and banners lining the road into most places that I wonder whether there is a legal requirement, i.e. to register a business, you are obliged to erect a ugly billboard or sign on the road into town.

It seems that, in Poland, if you’re setting up a business, then you don’t have many choices for the company’s name. In fact, there are only 3 options:

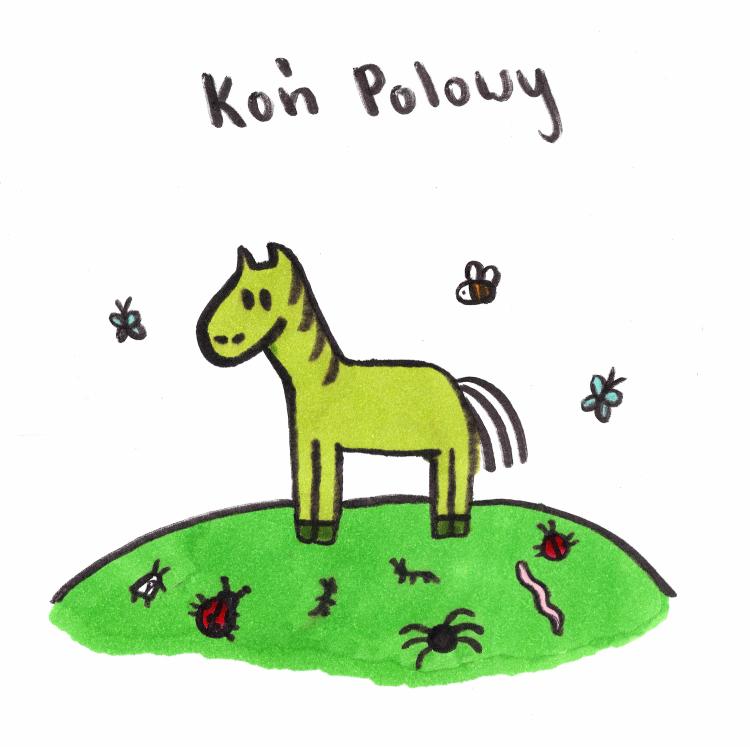

1. -pol

The first option is patriotic. You use the suffix -pol to show the world that your business is 100% Polish. This is especially true if you sell food:

- Szynkopol

- Indykpol

- Rybopol

For a logo, it’s common to use a cartoon of a pig, turkey, fish etc, happily dancing its way to the dinner table.

2. -ex / -bud

The second option is for a company that exports a product or service. In this case, it’s necessary to add -ex to the end of the name. The owners hope, rather optimistically, that this gives the company an international profile:

- Dachmex

- Żwirex

- Paletex

The only exception is the construction industry, then it’s necessary to use bud in part of the name:

- Drogbud

- Słupbud

3. Two Guys

The final option is used if two Polish guys are setting up in business together. In this case you take one syllable from each of their first names and join them together:

- Janmat = Janusz and Mateusz

- Zendar = Zenon and Dariusz

- Jarmar = Jarosław and Mariusz

To give another example, there’s a furniture company that operates in Poland called Juan. Because of the name, I assumed it was Spanish, but I later learned that it was set up by two guys from Warsaw called Jurek and Andrzej. Stupid me, forgot about the two guys rule!

If you are bored on a long journey, then you can play a game with these company names. It’s a great way to pass the time.

The rules are simple. The first passenger to spot a sign, billboard or banner with one of the above types of company names get the points. As you leave town, the person with the most points wins.

- -pol = 1 point + 2 additional points if there’s a dancing turkey, fish, pig as a logo

- -ex/bud = 2 points

- two guys = 3 points (but you have to say which two names were used)

By the way, if you’re playing this for the first time, avoid Radom, it’s for advanced players only – you’ll have 30+ points before you get anywhere near the city!