Ask a British person how many letters there are in the alphabet and they will instantly answer: twenty-six.

Ask a Polish person how many letters are in the Polish alphabet and they don’t know. Indeed, they don’t even care. The most typical responses are:

- who cares?

- never counted!

- why would I need to know that?

In Britain everybody knows some basic facts – there’s 1 sun in the sky, 4 points on a compass, 12 months in a year, and the first thing you learn on your first day at school is that there are 26 letters in the alphabet.

In Poland, no seems to give a damn how many letters there are.

It’s weird, shocking, even scandalous, and whenever I express this to a Pole, they don’t see the problem.

Without knowing how many letters are in the language, how can you type an email, decode the enigma machine or do something really hard, like play Scrabble?

I guess part of my shock is connected with the fact that I, as a foreigner learning Polish, had to get to grips with many additional letters. Yet Poles don’t even know how many there are!

Another enigma that surrounds the Polish alphabet are the phantom letters Q, V and X. They’re not in the language, but they show up from time to time and this confuses me.

V, for instance, isn’t in the written language, but does exist in body language – I’ve seen many Poles holding up two fingers to show the V for victory gesture. Is this allowed? V isn’t even in the Polish alphabet. Shouldn’t they make a Z for zwycięstwo gesture by drawing a Z in the air… or would people think they’re referring to Zorro?

Then, there’s X which appears in the names of countless Polish firms from Budimex to Metalex, while Q is present in Latin words such as Quo Vadis. So do the letters Q, V and X exist, or don’t they?

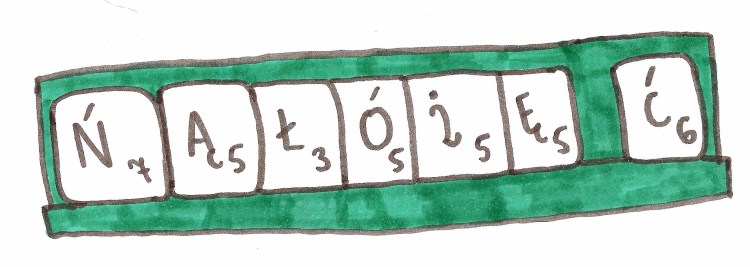

Foolishly, I once agreed to play Scrabble in Polish. An English native-speaker gets a surprise straight out of the box when you see the points on the letter tiles. In the English version, Z is worth 10 points while in the Polish version it’s only worth 1. The other most valuable letter in English is Q, which is worth 10, but isn’t in the Polish version. My usual strategy for winning – waiting until I can place the word q-u-i-z on a triple word score – just wasn’t going to work.

So I started with a short, simple word – just three letters J, U and Z to spell the Polish word for ‘soon‘:

Me: It’s on a triple word score, so 3 times 6 equals 18 points.

Opponent: There’s no such word, już is spelt with a Ż.

Me: Aren’t the Z’s interchangeable? I don’t have a Z with a dot.

Opponent: No, they’re completely different letters. One is worth 1 point while the other is worth 5.

Me: Oh come on. That’s pedantic. It’s the same letter. Looks the same, sounds the same and comes at the end of the alphabet.

Opponent: No, Z, Ż and Ź are different letters entirely.

Me: But I’m a foreigner, isn’t there’s some handicap system in which I can substitute a normal Z, S or C for the funny ones?

Opponent: No. They’re different letters. You can’t substitute a M for a W by turning it upside down!

Me: Fine, can I have ‘F-U-J?

Opponent: No, it’s not a word.

Me: Of course it is. That’s what foreigners say when they first see the Polish alphabet!

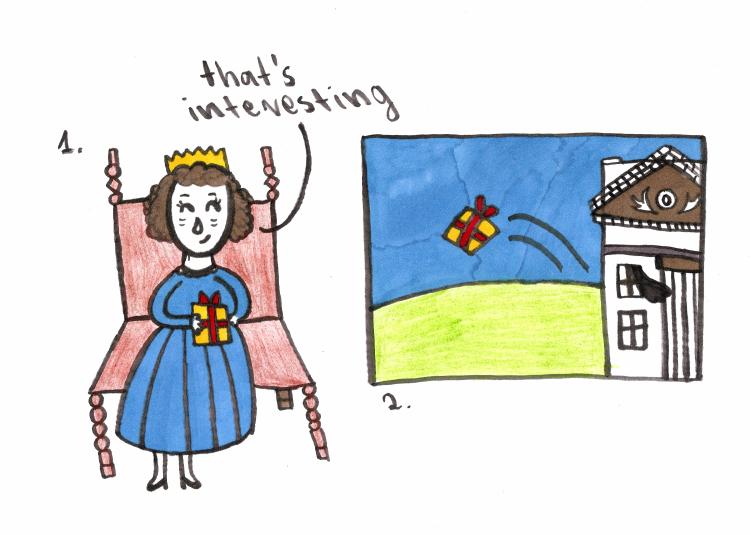

Okay I was being facetious – they look so cute that learners, when they first encounter the new letters, give them special names:

- funny E

- Z with a hat

- A with a tail

- L with a belt

I guess it’s because they look like Roman letters dressed up in Polish folk costumes with hats, belts, swords and feathers.

In Polish, some of the diacritical marks are called kropki and kreski (dots and dashes), and of course, dots and dashes are also found in Morse code…

…which makes me wonder…

…maybe Polish writing actually contains a hidden code?

Maybe thousands of encrypted messages are hidden in all those dots and dashes and funny tails?

I don’t want to sound paranoid, but what if the sentence ‘Czy świerszcze lubią jeździć na łyżwach?’ includes a hidden message to Polish readers, like ‘never let a foreigner beat you at Scrabble‘?

Just before World War II, when the Polish Army shared their intelligence on the Enigma machine with their British and French allies, did they share everything, or perhaps, did they keep something back?

Just like the number of letters in the Polish alphabet, and the phantom letters Q, V and X… it’s an enigma!