Poles use a lot of rhyming expressions in everyday speech, and when I once told a friend that I like these expressions and he said:

‘What can I say? We’re a nation of poets!’

So to celebrate this nation of poets, here are some of my favourite rhyming expressions connected to work:

w naszym fachu nie ma strachu

This means ‘in our profession there is no fear‘, and when I first heard the expression I took it literally as a claim by the tradesman that he is so brave that he can tackle any job.

And to be honest, I would be rather unsettled by such a show of bravado. If I had a choice, I wouldn’t employ any tradesman who made this claim. It’s asking for trouble!

I imagined that the last words of many Polish builders before they met an untimely death were ‘w naszym fachu nie ma strachu‘…just before he fell off the dachu!

Later I learned that it’s not meant literally, and that it’s an expression tradesmen use to calm the client when they ask if a particular job is possible. A good rhyming translation would be ‘no fear, the plumber is here.’

elektryka prąd nie tyka

Another favourite of mine, and another expression to add the category ‘famous last words of Polish workers’ is elektryka prąd nie tyka (electricity doesn’t bother an electrician)

As far as I understand, this expression is complete wishful thinking as the electrician believes he is immune to electricity. I don’t know whether Polish electricians are made out of rubber, or whether their reactions are faster than a spark of electricity, but I still fear that they might be a little over confident.

zdrowie na budowie

Given the bravado of the previous two expressions, when I first saw zdrowie na budowie, I took literally. I assumed it was a slogan from communist times and was probably printed on posters in the style of social realism. By looking after the safety of himself and his colleagues, our heroic brick-layer builds apartments in record time.

I also figured that, in response to all the foolish bravery shown by Polish workmen, it was necessary to come up with a way to remind electricians that they are not immune to electricity. Fortunately, in Polish the word building site happens to rhyme with health and so, in an easy day’s work for the copywriter, zdrowie na budowie was created.

Yet my incorrect assumptions didn’t end there.

I also thought it was nice that construction firms care so much about the well-being of their employees that they came up with this slogan. Of course, it’s fashionable nowadays to erect digital signs saying 127 days since the last accident on this building site. What’s more, modern corporations have programs to support the well-being of their staff, but it seems that Polish building sites were ahead of this trend. I wondered whether it extended beyond health to other more fashionable concerns like wellness na budowie or mindfulness na koparce?

Then one day I learned that this slogan isn’t about workplace safety…nor mindfulness on a fork-lift truck, but it’s actually a toast and that the full version should read na zdrowie na budowie.

So the expression does refer to health on the building sites, just not in the way I assumed. ‘To your health on the building site‘ is the actual translation.

Oh!

What else is there to say when it turns out that your assumptions were completely wrong and that the world is actually a lot more cynical than you that you imagined?

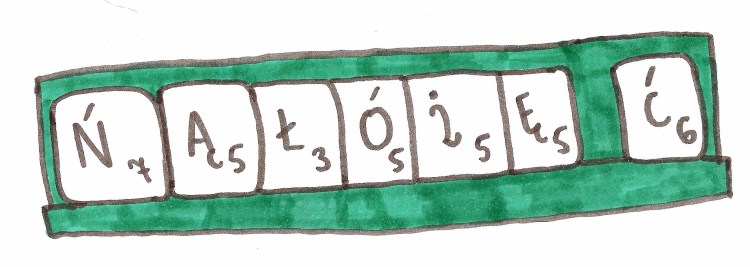

gdzie kucharek sześc, tam nie ma co jeść

In the spirit of ignoring workplace safety, this last expression concerns a situation in which it wouldn’t be a problem if half the workforce had an work-related accident.

In English we have a very similar expression: too many cooks, spoil the broth, and both languages agree that the less cooks, the better.

I don’t know what it is about the cooking profession, but both languages agree that chefs just can’t work together in the kitchen. Perhaps they should learn from the builders and open a bottle of sherry before they start work?

I’m disappointed that we don’t have an English expression that rhymes. Using the Polish format with a number of chefs, it’s a piece of cake to come up with some useful rhymes:

- when the cooks number eight, their soup you’ll hate

- when the cooks number five, you won’t stay alive

- when the cooks number four, just head for the door

I guess we’re just not a nation of poets…well our builders and cooks aren’t.

So if you’re working hard decorating your apartment or preparing food for Christmas in the kitchen, I hope your workplace is safe, free of fear and full of teamwork. If not, then there’s a simple solution…’na zdrowie‘.